Schedule

Team Canada (Men)

2026 Olympic Winter Games | Feb. 11-22, 2026

IIHF U18 Men’s World Championship | Apr. 22 - May 2, 2026

IIHF World Championship | May 15-31, 2026

Junior A World Challenge | Dec. 7-13, 2025

U17 World Challenge | Nov 2-8, 2025

IIHF World Junior Championship | Dec. 26, 2025 - Jan. 5, 2026

Spengler Cup | Dec. 26-31, 2025

Search

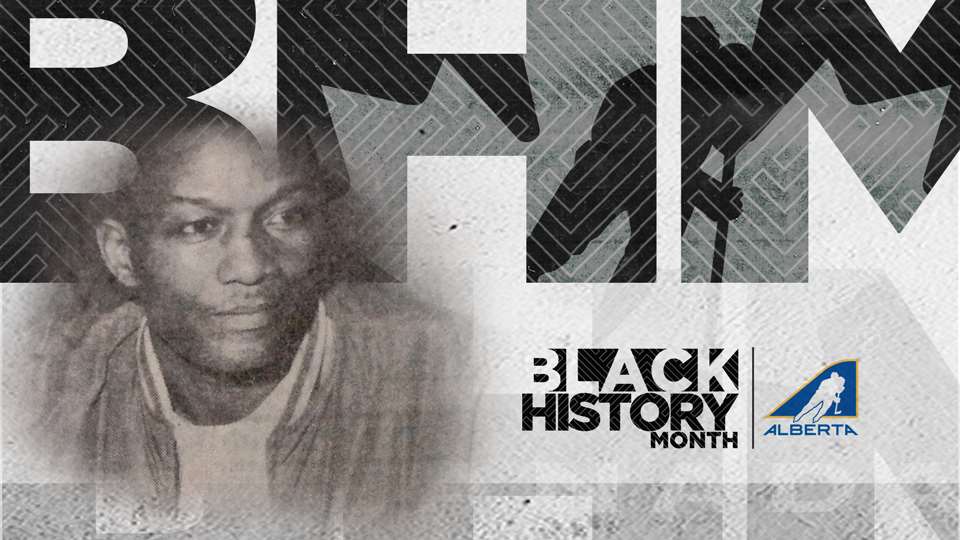

A living legacy

The roots of the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes run deep in the game’s past and present, and could help shape the future

For William James Riley, the passion for the game began in a typically Canadian way.

“I never missed Hockey Night in Canada,” Riley says.

“Every Saturday night, I was glued to the TV.”

When it came to choosing a team, he never really had a choice in the matter. A childhood pair of PJs sealed his fate.

“I curse my mother because she bought me a pair of Toronto Maple Leafs pyjamas,” Riley says with a laugh.

“But she got my brother a pair of Chicago Blackhawks pyjamas and, you know, the Blackhawks have won three or four Cups since then and my Leafs are still stuck on that one from ’67.”

Riley, better known in hockey circles as Bill, first laced up his skates as a young boy in his hometown of Amherst, N.S.

It was a long way from Washington, D.C., where he would make history with the Washington Capitals on Dec. 26, 1974 as the third Black player to skate in the National Hockey League and the first African Nova Scotian.

Reflecting on the Black hockey history of his native province, that distinction is one of immense pride for Riley, who was inducted into the Nova Scotia Sports of Fame in 1998.

“We had a lot of good Black hockey players,” he recalls.

“And not only when I was growing up, but the crowd in front of me, too. There were guys who came before me who were phenomenal but never got any offers or opportunities to play.

“I look back and I say, ‘How come none of those guys were ever asked to play for the senior team?’”

It has been said that Nova Scotia is the birthplace of Black culture and heritage in Canada. The roots of Black communities run deep throughout the province and, in some cases, date back more than four centuries.

It is a culture and history that Sgt. Craig Smith has been working to preserve. For the past five years, he has served as president of the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia.

An author and historian, Smith says it was only natural that hockey became a part of the Black experience in the province.

“My mom grew up in New Glasgow and she came from a family of 18,” Smith says.

“All of them, very early in their lives, learned to skate. You learned how to swim and you learned how to skate because the ponds and lakes were all around your homes. It’s the same for most of the Black communities in the province, especially those on the outskirts of town.

“And hockey just became an automatic for a lot of the men.”

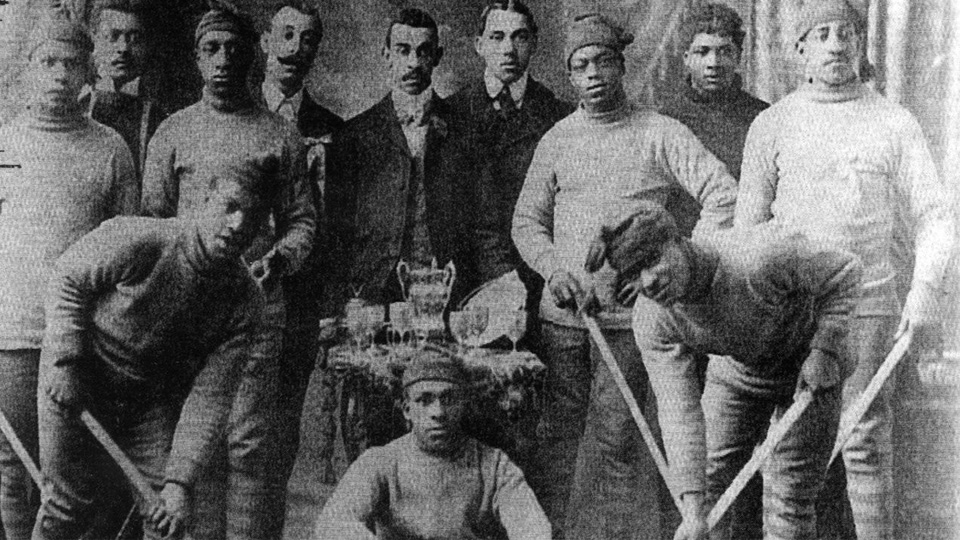

Just before the dawn of the 20th century, the relationship between the province’s Black community and the game was formalized. In 1895, a group of Black Baptist Church leaders and academics came together to establish the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes.

Formed more than two decades before the NHL, the league aimed to attract young Black men to the Church. The arrangement was simple: come to Sunday service, then play games against rival churches and communities.

Before it was even a decade old, the league had moved from ponds to local rinks and had grown to boast hundreds of players and a dozen teams from communities like Dartmouth, Africville, and Upper Tantallon. All-Black clubs from as far away as Riley’s hometown of Amherst and even Charlottetown, P.E.I., vied for the league title.

“You had Black men who, at a time when they were still fighting for the right just to be accepted in their own country as equal, were out playing hockey on the lakes and ponds and had formed their own league,” Smith says.

“You had Black men who, at a time when they were still fighting for the right just to be accepted in their own country as equal, were out playing hockey on the lakes and ponds and had formed their own league,” Smith says.

“It’s amazing when you just consider that and think about it for a moment.”

In its early days, games in the Colored Hockey League were played without a rulebook. Without those constraints, the league fostered a fast, physical and innovative brand of play, and its teams were said to rival their best white contemporaries.

It is believed that early variations of the butterfly style of goaltending and even the slapshot can be traced back to the league.

At a time when it was prohibited in the game that white teams were playing, diminutive goaltender Henry “Braces” Franklyn was dropping to his knees to stop pucks while the Halifax Eurekas’ Eddie Martin was raising his stick to his waist and slapping pucks at opposition nets. That was almost 50-years before Bernie “Boom Boom” Geoffrion popularized the shot with the Montreal Canadiens.

But the innovations of the Colored Hockey League were short-lived. Following decades of discrimination and racist government policies, a legal dispute in Africville over a proposed railroad annexation of their land pitted Halifax’s Black community against government officials.

During the ensuing five-year legal battle, league organizers struggled to secure quality ice from many local rink owners who refused to rent their facilities to the league. Games were ultimately forced back to the community lakes and ponds where the league had begun.

It is said that newspaper coverage of the league was halted almost overnight and so, too, was the league’s influence in the Maritimes.

The Colored Hockey League made a brief return in the 1920s but did not enjoy the reach and popularity it once had. By the Second World War, the league had been largely erased from Atlantic Canadian history.

“Some of those communities have kind of dried up, people moved away, and hockey became an expensive sport in my lifetime, so you don’t have as many Black people gravitating towards [hockey],” Smith says.

Interest in the league was revived in 2004 when Black Ice: The Lost History of the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes, 1895 to 1925 was released by George and Darril Fosty.

The book caught the attention of Wilf Jackson, who had never heard of the Colored Hockey League. Inspired by the Black community’s forgotten roots in the game, Jackson and his late wife Olive, who they had learned had family members who played with a team in Truro, worked with other volunteers in their community to establish the Black Ice Hockey and Sports Hall of Fame Society

They also collaborated with Hockey Nova Scotia to launch the Black Youth Ice Hockey Program.

The program’s goal is simple: to remove barriers and make the sport more accessible for a community that, today, is underrepresented at Nova Scotia rinks.

“The game changed for us,” says Jackson, the current president of the society. “And now we just want to get back in the game.”

In the 12 years since it was established, more than 300 young Black Nova Scotians have learned the fundamentals of hockey thanks to the program. Each year, its popularity seems to grow and in 2019, Sidney Crosby donated dozens of full sets of equipment for its participants.

“It’s just great because when we started it, I thought if we could get a handful of kids, that would be successful,” Jackson says.

It has been almost a century since the Colored Hockey League ceased operations, but Sgt. Craig Smith believes its lasting impacts can still be felt today, even at the highest levels of the game.

“Evander Kane has family in both East Preston and North Preston, Devante Smith-Pelly has family in Guysborough, and Wayne Simmonds has family in North Preston,” Smith explains.

“When you look at these guys who are in the NHL today, as well as those guys like Pokey Reddick and Bill Riley, and those who came before them, you have to link their stardom and their opportunity for stardom in some ways to the Colored Hockey League.”

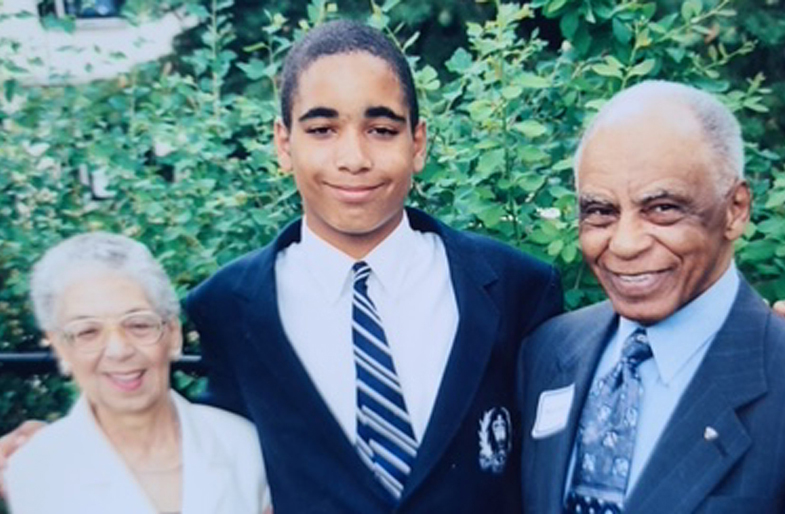

Riley knows that firsthand. His grandfather Fred competed for a Colored Hockey League championship with the Amherst Royals during the early 1900s. But the elder Riley was reluctant to discuss his experiences with his grandson, a burgeoning star in the local hockey scene.

“All he could tell me about the league was all of the doors that were slammed in their faces,” Riley recalls.

“I know he didn’t like to do that because he felt like that would deter me from reaching out and fighting for my goals.”

Discrimination and racism were a reality for the younger Riley, too, throughout a hockey journey that brought him through the Junior A and Junior A ranks in Nova Scotia, the British Columbia Senior Hockey League, the International Hockey League, the American Hockey League and eventually the NHL.

“There was certainly adversity,” he says. “Especially when you went out of town to play.

“There were a lot of things that happened and a lot of things that were said that I had to keep inside because I didn’t want to rock the boat for the Black kids behind me.”

But even that racism and hate could not deter the hardworking and respected right-winger, who would spend parts of five seasons in the NHL with the Capitals and Winnipeg Jets, scoring 31 goals and adding 30 assists in 139 career games.

He later captained the AHL’s now-defunct New Brunswick Hawks to a Calder Cup championship in 1982.

Riley is proud, too, that he wasn’t the last talented Black player to come out of his old neighbourhood.

Amherst’s Craig Martin was drafted by the Winnipeg Jets in 1990 and Mark McFarlane, a Memorial Cup champion with the Swift Current Broncos in 1989, was a veteran of the minor league circuit.

“That’s unheard of because that’s three Black players who played pro that came out of one little neighbourhood in Amherst, and all three kids went through the Nova Scotia hockey system,” Riley says.

“And we were all descendants of the Colored Hockey League.”

It’s a legacy that remains very important to Riley, a man who helped blaze the trail for the next generations of Black NHLers like Mike Grier, Anson Carter, Evander Kane and a favourite player of his who now plays for his childhood team.

“Man, I have got to tell you, I love Wayne Simmonds and I was so happy when Toronto got him.”

“I jumped up and hit my head on the ceiling when he scored his first goal with a Maple Leafs jersey on.”

This Saturday night, you can probably find William James Riley in the same place you could when he was a boy: in front of the TV. Like the Black community in Nova Scotia, his roots in the game run deep, and this weekend, yes, he’ll be rooting for his favourite team.

But these days, it has taken on a little added meaning. These days, it might be about more than just a pair of pyjamas.

For more information: |

- <

- >

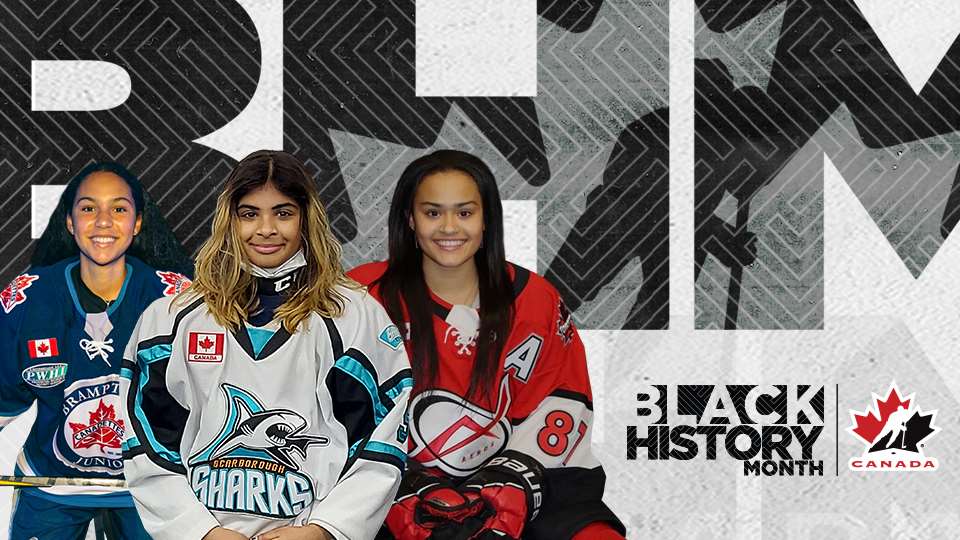

Emma Maltais, who played with Jaques at Ohio State, was more than happy to

welcome her friend to the national team. Before the game, it was Maltais who

handed Jaques her Team Canada jersey.

“Sophie’s been dreaming of that moment for a long time,” says Maltais.

“She’s so humble and for someone who is so good, there’s a calmness to her

while she plays at such a high level. She’s so driven as a person too, in

athletics and academics, and that speaks a lot to her as a person and her

willingness to go the extra mile to find success.”

Emma Maltais, who played with Jaques at Ohio State, was more than happy to

welcome her friend to the national team. Before the game, it was Maltais who

handed Jaques her Team Canada jersey.

“Sophie’s been dreaming of that moment for a long time,” says Maltais.

“She’s so humble and for someone who is so good, there’s a calmness to her

while she plays at such a high level. She’s so driven as a person too, in

athletics and academics, and that speaks a lot to her as a person and her

willingness to go the extra mile to find success.”

Andrea Murray

Hometown: Mississauga, Ont.

Andrea Murray

Hometown: Mississauga, Ont.