For countless generations, my family lived in Punjab, India. They were

honest, hard-working, salt-of-the-earth people. Each generation took over

the farming and continued the family traditions and lifestyle.

My dad had a different dream for himself and for his future family. A dream

to come to Canada and start a new life with new opportunities. But he never

imagined that his Canadian dream would include hockey.

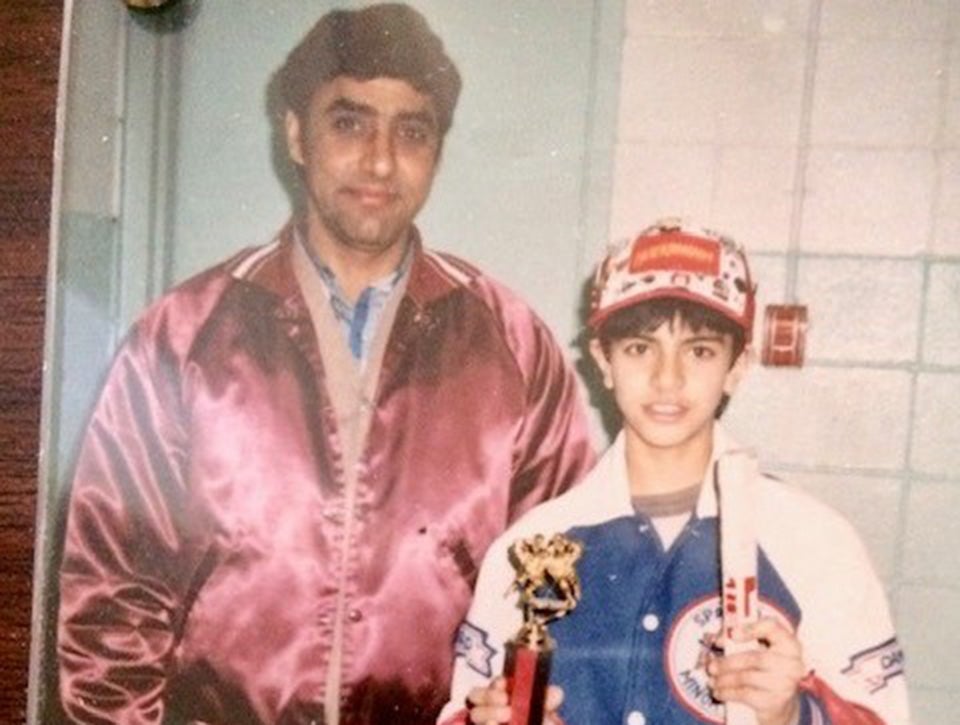

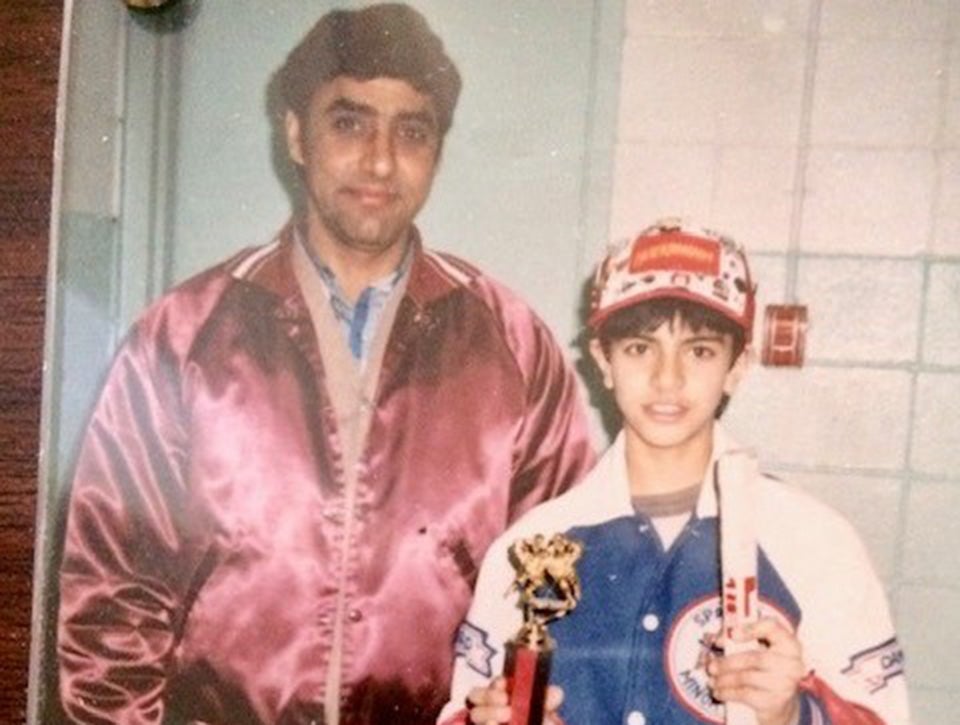

At the age of four, I vividly remember sitting on the front step of our

townhouse in Sparwood, B.C., the town I was born in, watching a group of

older boys play street hockey. I was instantly intrigued. My dad recognized

my interest and bought me a plastic hockey stick with a pink blade, yellow

shaft and a black rubber knob, which also came with two plastic pucks. I

would play non-stop in our undeveloped basement, shooting into a milk

crate.

As the hockey season approached, we were fortunate enough to have older

East Indian family friends whose boys played minor hockey in Sparwood, so

my dad registered me. There was only one problem – I had never been on

skates.

I was incredibly lucky to have a great skating instructor; his name was

Tander Sandhu, and he was 11 years old. He says it took me 15 minutes in an

old pair of his skates that weren’t even my size to start skating on my

own. By the age of eight, I was moved up to play with the older kids after

scoring 21 goals in two games.

I kept scoring several goals per game, and then early in the season when I

was 11 years old, they implemented a rule that players could only score

three goals in a game. Even though I was a playmaker and had a lot of

assists, it was pretty well-known that this rule was created because of me.

In hindsight, it made me an even better passer; however, my family always

wonders if that rule was not implemented how much more attention and

exposure would I have received in the hockey community.

I was born in Canada, and simply loved the game. I saw all my teammates and

their families in the same manner, but not everyone looked at me as an

equal. As a kid, perhaps I was oblivious to the looks and comments. The

racism piece really came to light when I was eight. After my third goal, a

player on the opposing team, who was from a nearby town, yelled something

at me several times while I was taking the face-off against him. A word

that started with the letter P, but I couldn’t fully understand what he was

saying.

After scoring two more goals, he continued yelling the same word at me over

and over again. I can still see what he was wearing, his facial expressions

and his anger. I remember feeling scared. I didn’t know what I did wrong,

and why he was so upset with me. My teammate told me he was saying

something really bad about me. Something about how I look. The taunting

continued, but I managed to focus on playing the game and having fun. After

finishing the game with 13 goals, he shook my hand and said the word ‘Paki’

yet again, right to my face.

All weekend the incident rolled through my mind. On Monday morning at

recess, I asked my older East Indian friend, who also played hockey, what

‘Paki’ meant. He explained that is what they call us in a negative way to

make fun of us. It was a name assigned to me because of the colour of my

skin.

I got used to hearing it over the years. However, the worst had to be

hearing from a parent when I was 15 years old. Just before the game

started, with the arena pretty quiet, the father of the opposing goaltender

yelled to his son, “Don’t let that f*cking Paki score!” and then looked

straight at me with glaring eyes.

Towards the end of that season, we went to a small town in Crowsnest Pass

in southern Alberta. It was a Friday night game, and a bunch of teenagers

came to cheer on their home team. Instead of watching the game, they stood

away from the parents and threw constant racial slurs at me while making

inappropriate gestures.

I have never repeated what they said. But if we want to invoke change, we

need to be honest with what was said and done. They were saying things

like, “Go back home, Paki,” or “Put curry on the puck, it will slide

better,” or “Where is the red dot on your forehead?” Any time I took a

face-off in front of them, or simply skated past them, they banged their

hands on the glass and tried to scare and intimate me.

We won 6-4 that night. My parents were so happy on the car ride home, as

they thought I played well; however, I was quiet and numb. When I got home,

I had tears in my eyes and asked my parents, “Who cares about the game, did

you not see what was happening?” They told me that if I wanted to be an

elite player and represent our culture, it was something I would need to

endure. My dad then told me some stories of the racism he had gone through

on the streets and in the workforce. He wanted to shield me from it, but

sadly he could not.

It was then that I really started to envision that one day I would use

hockey to earn respect, and then turn around and help other South Asian

players and their families.

I had the goal of playing professional hockey, but as we all know, the path

to get there is extremely complicated. With immigrant parents, no mentors

and no internet, navigating the hockey system was very difficult. Some how,

some way, I made it through Junior B to Junior A and to Concordia

University College in Edmonton. But I started to doubt that college hockey

was the right decision to get me to my goal.

After a few games, an ex-NHL coach turned agent named Bill Laforge Sr. came

to watch us play. He was gracious enough to take me under his wing and send

me on my way to play pro hockey in the United States.

In my seven-year career, I played five seasons with the Tacoma Sabercats in

the West Coast Hockey League (WCHL), where I had two stand-out coaches:

three years with John Olver and two with Robert Dirk, who I coach with now

at the Okanagan Hockey Academy.

During this time, I really grew not only as a hockey player, but as a

person. I learned the importance of community work and giving back. The

city showed me a lot of love in return, which overshadowed any

discrimination. I won the WCHL championship with the Sabercats in 1999,

played in the WCHL All-Star Game and was voted Most Popular Player by the

fans in all five of my seasons.

A few other milestones were getting called up to play in the International

Hockey League (IHL) with the Las Vegas Thunder, and the following year,

signing a two-way contract with the Hamilton Bulldogs of the American

Hockey League (AHL), an affiliate of my favourite team, the Edmonton

Oilers.

I hung up my skates at the end of the 2002-03 season and knew I had to

fulfil my other goal of paying it forward and giving back.

When my now-16-year-old son started playing Timbits, I got involved in

assisting, educating, mentoring and coaching our South Asian youth and

their families. A few years later, I delved deeper into women’s hockey when

my daughter started playing. I was lucky enough to help take this

internationally when a women’s team from Leh Ladakh, India, came to Canada

for the first time to participate in WickFest, run by Team Canada icon

Hayley Wickenheiser.

In the end, my passion for the game comes back to providing support and

guidance to South Asian and other ethnic players, connecting the community,

highlighting players and parents, and spreading information.

It was through my work with the South Asian community that I was honoured

in 2020 to receive the Willie O’Ree Community Award, becoming the first

South Asian to win an NHL award, which really drove me to continue to make

an impact in the diversity and inclusion component of the game.

Already, we see a number of NHL teams recognize the contributions of the

South Asian community by holding a South Asian Heritage Night. I have had

the privilege of being part of the Honour Guard or dropping the puck for

the Los Angeles Kings, Winnipeg Jets, Edmonton Oilers and Calgary Flames.

Change is slow, but where there is a will, there is a way. Together we will

help improve hockey culture and grow the game we all love. Just like in my

hockey journey from the age of four to when I played my last professional

game, perseverance and resilience are important factors.

Any road to success will always be under construction.

As Pak takes the next step into his hockey career, at the Centennial Cup

this weekend and into a busy summer, he is understanding the importance of

becoming a leader in hockey as well. Growing up in Oakville, he has seen the

diversity of hockey grow and hopes that the trend continues.

As Pak takes the next step into his hockey career, at the Centennial Cup

this weekend and into a busy summer, he is understanding the importance of

becoming a leader in hockey as well. Growing up in Oakville, he has seen the

diversity of hockey grow and hopes that the trend continues.